How We Bring the Ocean to Life in Epoxy

Some projects start as a simple idea and turn into a whole world. That’s what happened here. We set out to build a series of aquarium-style dioramas, each with its own story: divers exploring a wreck, the cold depths of a Mesozoic sea with prehistoric predators, or whales gliding past in quiet water. Each scene is a small universe that looks still, yet feels alive.

A World Under Water

One piece takes you back to the Mesozoic. We recreated a dark, heavy ocean full of life that no longer exists: a huge pliosaur attacking a plesiosaur, nearby ichthyosaurs, slow drifting jellyfish. The deeper you look, the more the scene pulls you in—figures fade into darkness and feel endless.

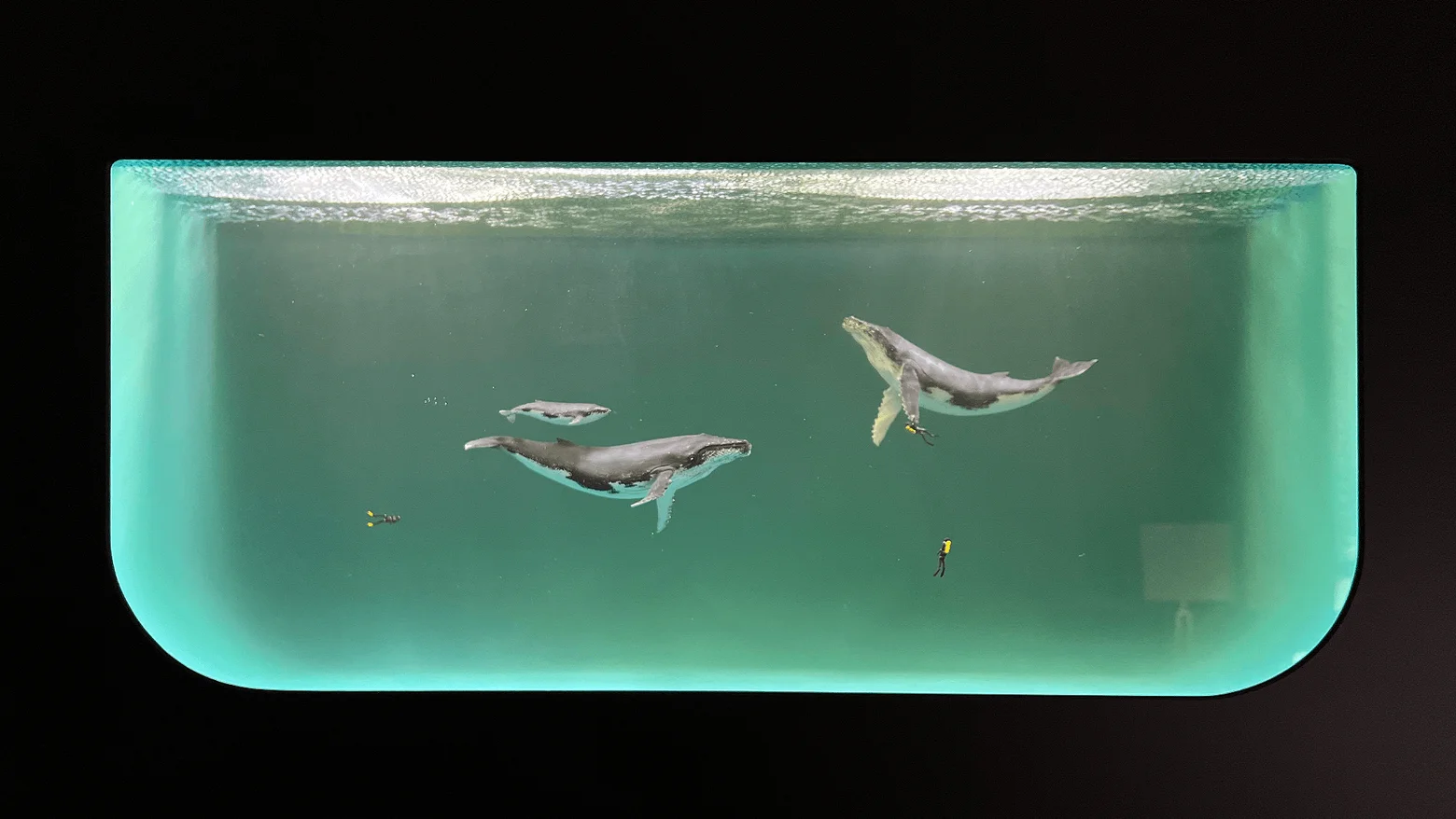

Another aquarium is calm and balanced: a dive with whales. We focused on skin texture—folds, scars, subtle color changes. In soft light the bodies feel real, and the surface finishes read like moving water.

A third piece leans into adventure: a wreck on the seafloor, broken masts, rusted deck plates. Divers sweep the hull with lights, revealing fragments in the dark. The lighting bends through the epoxy and creates a gentle sense of motion, as if the water is actually shifting.

Taming Epoxy

From the outside it looks easy: mix resin and hardener, pour, done. It comes in buckets—just mix and pour where you need it. So why do so few people attempt epoxy dioramas? Because the process is unforgiving and full of risks.

Miss the ratio and the resin can overheat, turn cloudy, or crack. Our rule of thumb: no more than 1.2–1.6 inches (3–4 cm) per lift. Go thicker and the temperature spikes, bubbles form, or stress cracks appear.

Degassing is critical. We use a vacuum chamber, then give the surface a quick pass with a torch to pop microbubbles. Even a few can ruin clarity and kill the “water” effect.

Ambient conditions matter. In summer the resin can kick too fast; in winter it may stall. We adjust batch size and temperature, cool the mix when needed, keep a log, and test. It’s closer to lab work than craft—milliliters and minutes matter.

Big volumes also raise safety issues. Raw epoxy isn’t very smelly, but sanding and heat release fumes and dust. We always use PPE, filtration, and ventilation—just like buckling a seat belt. The finished piece is safe: once fully cured, the resin is inert and doesn’t off-gas.

Projects at this scale take time and patience. One diorama takes two to four months, most of it pouring and curing. Each lift has to fully polymerize and settle before the next. It’s a slow, methodical process; rushing ruins it. We pour vertically so layers fuse into a single block with no visible lines. When the form finally comes off, we sand and polish to a mirror finish—only then does it read as real water.

Getting Real Depth

The idea for “aquarium dioramas” with a true sense of depth came from client requests. One client asked for a slice of “Alaska” — dark, deep water fading into lighter, clearer layers near the surface. A fully clear block looked flat; a single muddy tone felt dead. We switched to a gradient pour: a smooth color transition like real water.

We ran dozens of tests and only around the twentieth did we lock in where “depth” should start and where the light should fade out. The result is a convincing falloff: objects dissolve into darkness below while the top stays crystal clear. You read it as a real underwater scene, not a solid block.

Before the long pour schedule even starts, we build the scene itself. Marine animals, plants, wreck details — that’s the work of our 3D modelers and painters. The models need to hold up under close viewing; even with a gradient, the “aquarium” is essentially transparent, and every shortcut shows.

Lighting That Brings It Together

Lighting is the final touch—and it’s what makes the scene feel alive. We built a system that mimics underwater sunlight: a motor spins a perforated disk in front of a light source, throwing moving caustic patterns across the surfaces. The effect reads so naturally that it sometimes looks like real water is flowing inside.

We found it by accident when a piece sat near a window and sunlight started “playing” across the resin. Now we integrate the effect into every aquarium; a small detail that makes a big difference.

Working with epoxy takes patience, experience, and a bit of stubbornness. We’ve had layers crack, colors drift, and temperatures run hot. Each failure led to a better recipe and a more reliable process.

We approach these builds as both engineers and artists—measure, mix, sand, test—until the scene reads as a real underwater space you want to keep looking at.

When the lights come on and people go quiet for a second, that’s the moment it stops being a model and turns into a window—water that seems to move, time that seems to pause.

Thank you for reading.

If you found this useful, please support the author.

Tip the author